Back Story: A couple of months ago, while Arjay and I were in an elevator in a mall, we overheard a mom and her son talking about what transpired during graduation (a graduation ceremony was held earlier that day in the mall). I got intrigued, and a little bit furious, about what the mom told her son. Apparently, the kid didn’t get the highest award in their class. If that was my child, I would tell him that he did his best and that maybe he can do even better next time so he can get the highest award. But no. The mom said, “Sipsip kasi ‘yang kaklase mo sa teachers.” It’s like teaching the child that his failure is other people’s fault. You didn’t get what you want? Blame other people. What will that make of our children?!

When I was younger, I dreaded the end of the quarter wherein we have to bring home our report card to our parents for them to sign–I dreaded it especially when some of my grades declined. My mom always expected me to get 90s in my subjects so when I see 80s (or worse, 70s–gah! Trigonometry!) on my card, I get really nervous because I know we’ll be having the talk.

When we do have the talk, my mom would ask me, with that scary poker face of hers, why I’m not doing well. I don’t ever remember blaming the teacher for my grades. Instead, I’d tell her honestly that it’s because I didn’t understand the lesson well and that I will review better next time. And I did. Time and again, I would improve on how I review my lessons to maintain my grades. I’d spend extra time after classes reviewing, while I wait for my school service to pick us up from school. When I reach home, I’d review again. I also review on my way to school, during recess, during lunch time. Sometimes, I’d ask my classmates for help. Oftentimes, I would ask the teacher. I didn’t graduate the best in my class, but the biggest reward I got is knowing that I did my best.

I remember sometimes feeling jealous about my cousins because their parents were more laid back when it came to their academics. Their schools didn’t pressure them as much too. While they hung out with friends after school, I was studying. But looking back at it now, I’m glad I went through that kind of pressure in Assumption then in Ateneo. They trained me well–not just in academics, but in life. Ateneo especially. It’s where I learned to stand on my own, to fight my battles on my own. And it’s not so much about the grades in the end; it’s knowing that you failed, but stood up and tried again.

“You are not your grades. Numbers do not define who you are and who you will be,” a terror professor said on the last day of our class with him. This was right after we cried our eyes out because he made us watch Wit, which taught us an important lesson about life:

Nothing but a breath–a comma–separates life from life everlasting. It is very simple really. With the original punctuation restored, death is no longer something to act out on the stage, with exclamation points. It is a comma, a pause.

And this is not just about death, but also about failures. Failures do not end with a period, but a comma, a pause, after which we come up for air again. To try again.

It was difficult, but it prepared me for real life. A lot of people who knew me back when I was a kid are always so surprised at how I turned out. Tawag nga sa akin ni Arjay, SarCom. May Sariling Command. Haha! They didn’t expect me, that little girl who was always hiding behind my mom, to turn out to be a fearless pursuer of dreams, a fighter. Even I am surprised at myself! I never thought I can be this brave.

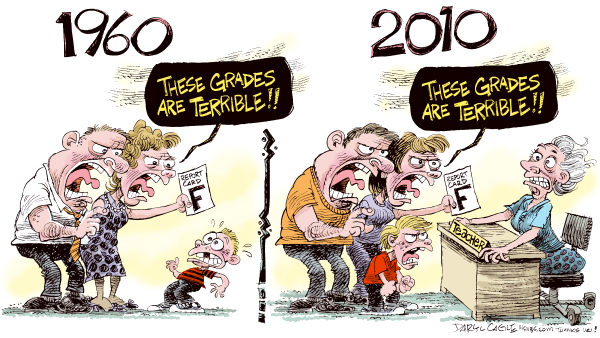

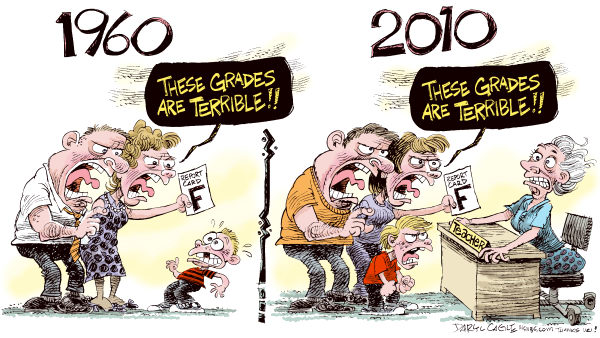

That’s why, at a young age, I already let my children experience pressure, failure, and defeat. If my daughter didn’t do well in class, I don’t go barging into the school demanding the teacher to explain herself for my daughter’s failure. Instead, I ask the teacher for advice on how we can help our daughter improve. Then, we talk to our daughter and encourage her to practice on what she needs to improve. We remind her to do her best (and to keep trying if she doesn’t get it the first time), even if it’s difficult or boring, in whatever she’s doing. It may just be writing numbers correctly now, but it’s a start for bigger things in the future.

We’re well-intentioned as parents, wanting to keep our kids happy and feeling good about themselves and their accomplishments. But when kids don’t experience what it’s like to fail, they miss the opportunity to learn from their mistakes and know how to improve for the future. (READ FULL ARTICLE HERE)

You see, I don’t want them to grow up as whiny kids who get whatever they want because mom and dad are always there to make sure everything will go their way. I don’t want to raise children who blame everyone but themselves when they fail. Admit it, we’ve got so many whiny kids around these days! I don’t want my children to be one of them. Although we are always behind them, ready to help them pick up the pieces, I want them to learn to be strong in times of pressure; to fight their battles on their own.

Some may think it’s harsh to let a 4-year old and 3-year old experience pressure, failure, and defeat at such a young age, but when do we let them experience it? When they’re out there, on their own? As early as now, we ask them to process situations. Instead of saying, “Don’t worry, Mommy and Daddy will take care of it,” we ask: Why didn’t it go the way you had planned it to? What are you going to do about it?

We have two choices of when our children can fail: now or later. Now, they are still in a safe environment with people willing to help them succeed. Later, it will be in the context of the workplace or with their own families when the stakes are much higher. (READ FULL ARTICLE HERE)

I have nothing against parents who prefer a different path for their children. But for my kids…well, I prefer that they feel loved, than feel special or entitled for anything. I’d rather they work hard for their own achievements instead of us laying everything down for them.